Mapeando la huelga feminista

In English

Desde el 2017, el 8 de marzo—el día internacional de la mujer trabajadora—se ha conmemorado con potentes huelgas feministas, que inventan nuevas prácticas y geografías de la huelga, haciendo paro tanto en trabajos (mal)pagados como en el trabajo doméstico y de cuidado no remunerado, rechazando los mandatos de género que distribuyen las tareas de forma desigual y que nos quieren dictaminar nuestro papel y potencial. A su vez, la huelga produce un tiempo de encuentro, para encontrarnos y elaborar nuevas formas de estar juntes, tejiendo nuevas alianzas y conexiones entre distintas luchas.

Sin embargo, la pandemia, y la consecuente crisis económica social, conlleva un conjunto de nuevas dificultades a la hora de parar. Ya sabemos que la pandemia afecta a las mujeres de forma más intensa. Ya sea en las primeras líneas de los hospitales y centros de salud, o en trabajos llamados esenciales sumamente feminizados y mal pagados, de la educación o el cuidado, o encerradas en el espacio doméstico por la cuarentena, convirtiéndonos en maestra, cuidadora, cocinera, todo a la vez y por tiempo completo, somos las mujeres que estamos poniendo los cuerpos contra la virus y la crisis.

Entonces, como paramos en el medio de una pandemia?

A partir de nuestra llamada a realizar mapas-derivas de la cuarentena, proponemos este ejercicio de mapeo como un método para repensar y rehacer tu/nuestra huelga. Se puede hacer sola o con grupos de amigues y compañeres, se puede dibujar sobre papel en blanco, o sobre un mapa base, hacer un collage o un diagrama del uso de tiempo, usar íconos o pegatinas. Los resultados se pueden compartir con nosotres (countercartographies(@)gmail.com) y en sus propias redes.

* Dibuja un mapa de tu vida cotidiana: ¿A dónde vas? ¿Dónde/cuándo trabajas? Trabajo remunerado, no remunerado, mal remunerado, etc. ¿Cómo (y quién) extrae valor de tu vida cotidiana? ¿Cuándo, y dónde, no trabajas?

* Mapea tus redes: ¿En qué redes de cuidado estás sumergida? ¿Quiénes trabajan para sostener tu cuarentena? ¿Y tu trabajo, a qué cuarentenas sostiene?

*¿Cuál es tu huelga? Mirando tu mapa de todo tu trabajo, ¿cómo vas a parar? ¿Dónde y cuándo vas a parar?

* ¿Qué hace falta para hacer posible tu huelga? Sabemos que no se puede parar sola. Sabemos que el trabajo de cuidado que hacemos en necesario en términos vitales, y, sin embargo, tenemos que parar. ¿Puedes imaginar un mapa de las conexiones, los apoyos, las infraestructuras, que harían posible tu huelga?

Map (y)our feminist strike

Since 2017, March 8—International Working Women’s Day—has been commemorated by powerful transnational feminist strikes, inventing new practices and geographies of the strike, striking as much from (under)paid work as from unpaid domestic work, as from gender mandates that distribute labor and attempt to discipline us. In turn, the strike produced a time of encounter, for us to find each other and elaborate new ways of being together, weaving new alliances and connections between our different struggles.

Yet, this year, the pandemic and corresponding crisis brings a new set of difficulties. We already know that the pandemic hits women the hardest. Whether on the underpaid front lines in hospitals and health care centers, the education and service work deemed essential, or trapped in the domestic space due to quarantine measures and job loss, becoming full-time teachers, cooks, care-givers, women are increasingly putting our bodies on the line.

So, how do we strike in this context?

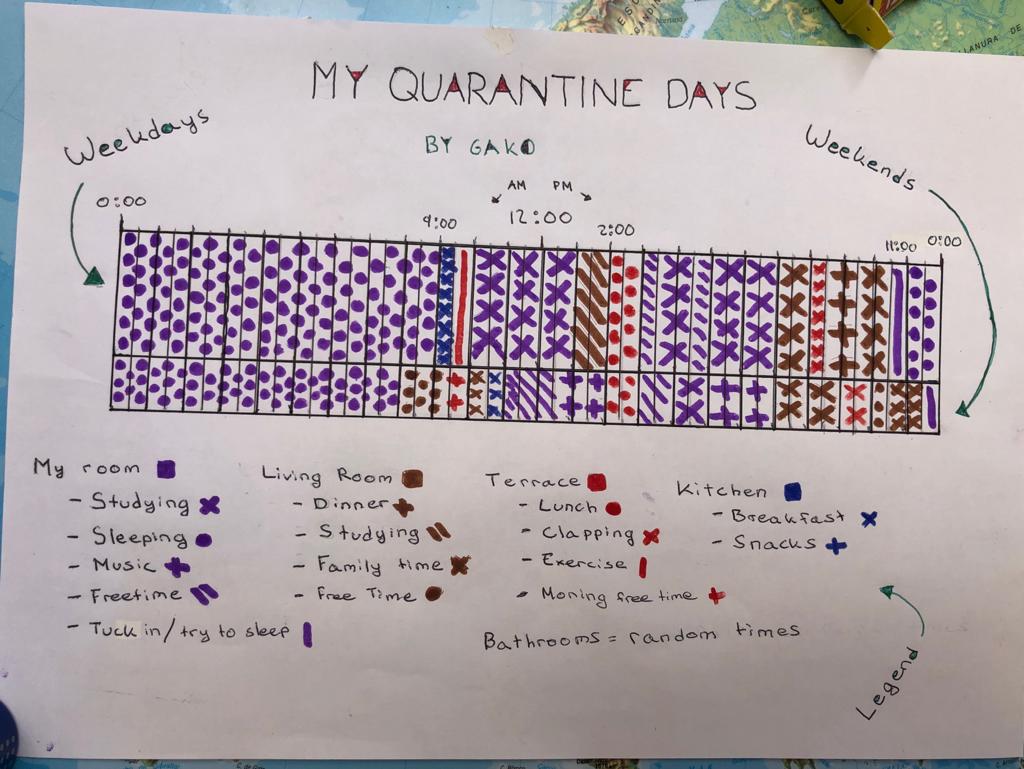

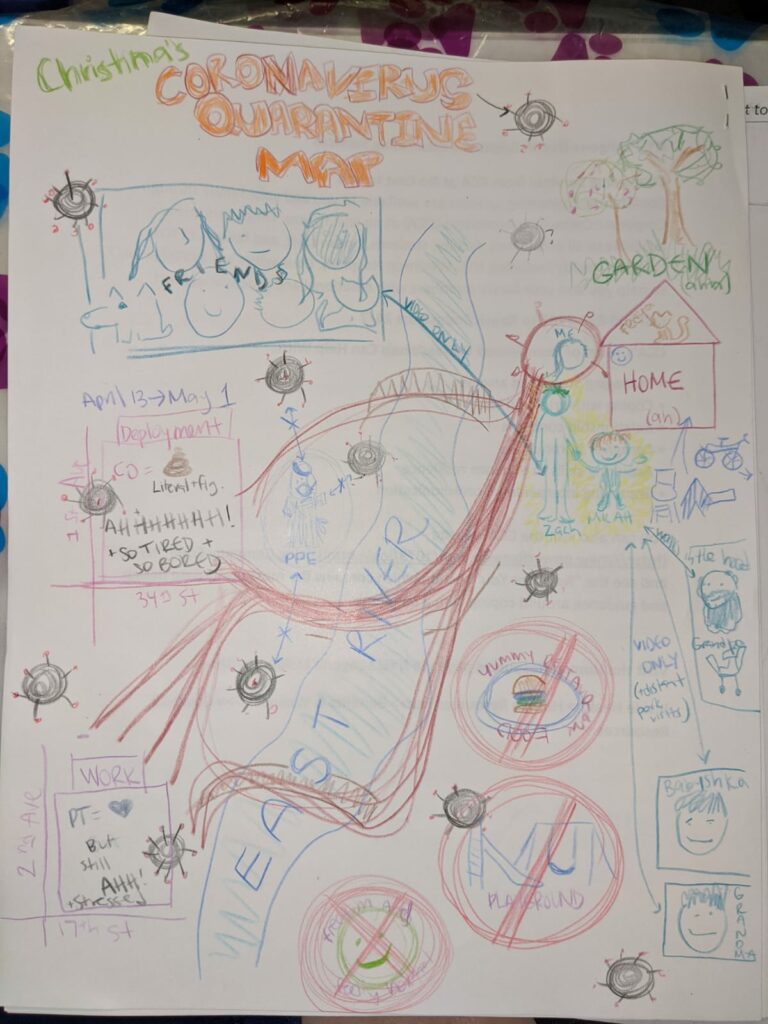

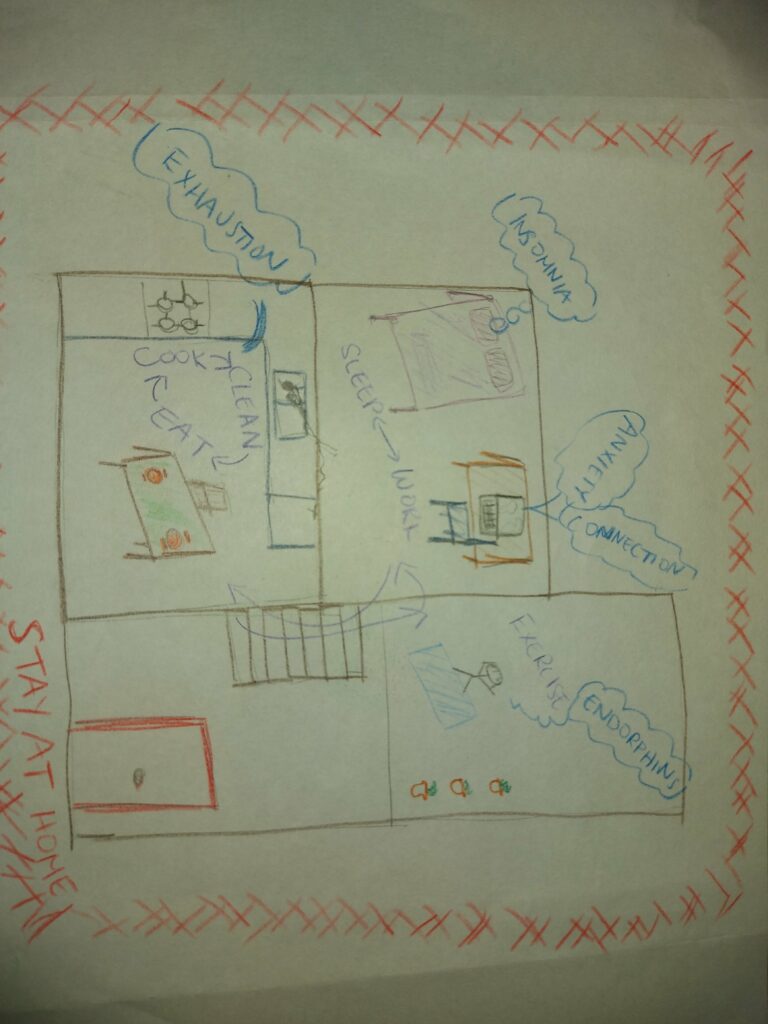

Building on our call for quarantine maps, we offer this mapping exercise as a way to start thinking about what (y)our strikes might look like. Do it alone or together, with groups of friends or compañeras, share the results with us (countercartographies(at)gmail.com) and each other, as you like. Draw directly on blank paper, make your own additions to a base map using stickers, icons, or collage. Make a time-use chart of how you spend time or another type of graphic representation of your life, work, and strike in the pandemic.

* Map your daily life: Where do you go? Where/when do you work? Paid work, unpaid, underpaid work. How is value extracted from your everyday life? When, and where, don’t you work?

* Map your networks: What networks of care are you embedded in? Whose labor sustains your quarantine? Whose quarantine does your labor sustain?

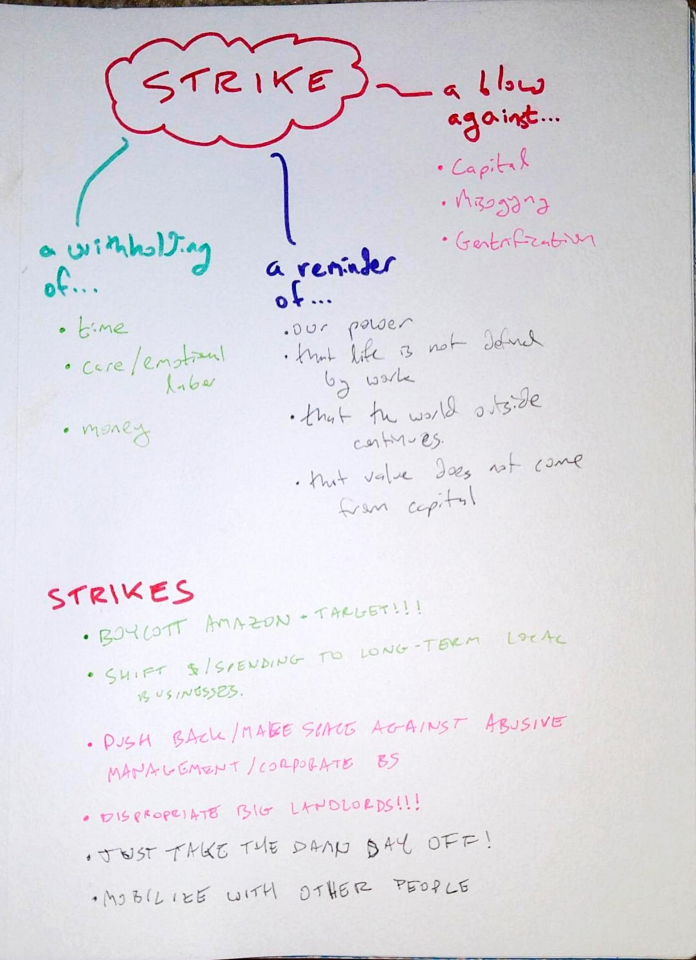

* What is your strike? Looking at your map/diagram of all your labor, how will you strike? Where/when will you strike? What will you strike against, what will you strike for?

* What would it take to make your strike possible? We know we cannot strike alone. We know that the care work we do is vitally necessary, and yet, we must strike. Could you imagine a map of connections, support, the infrastructure, that would make your strike possible?

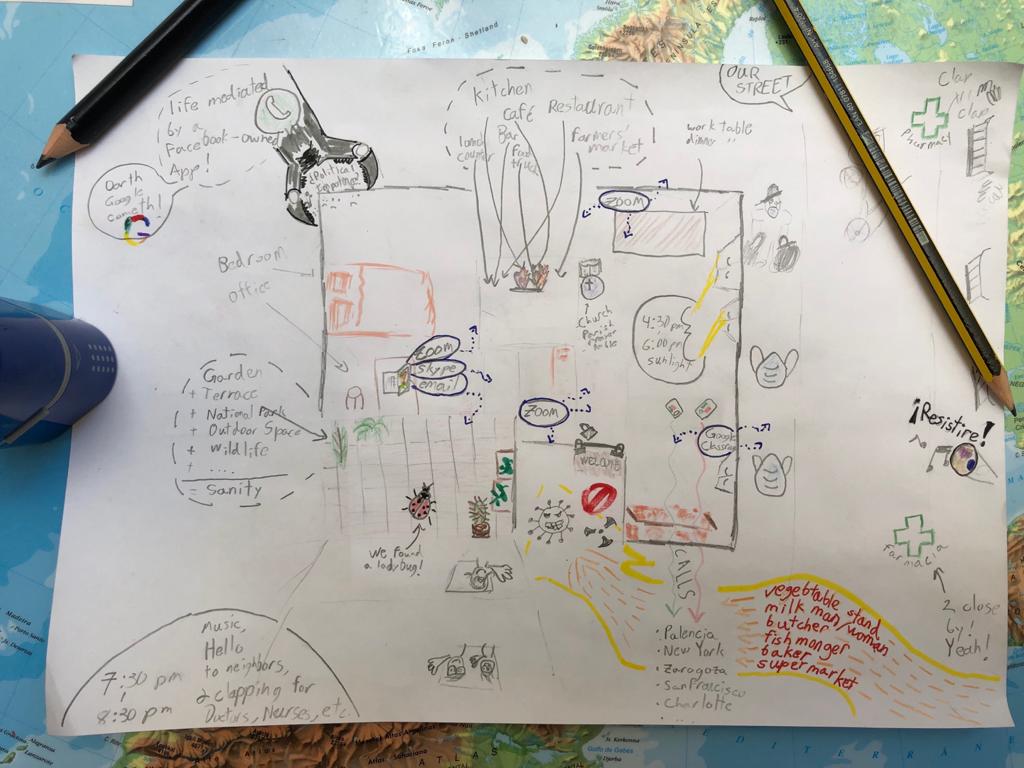

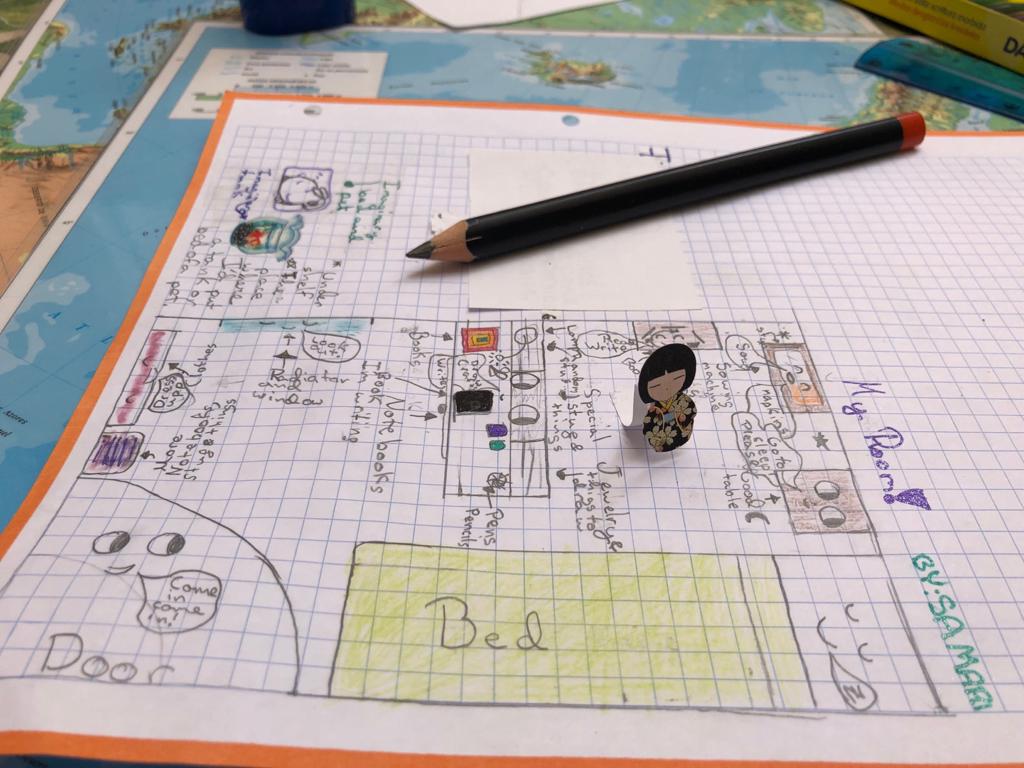

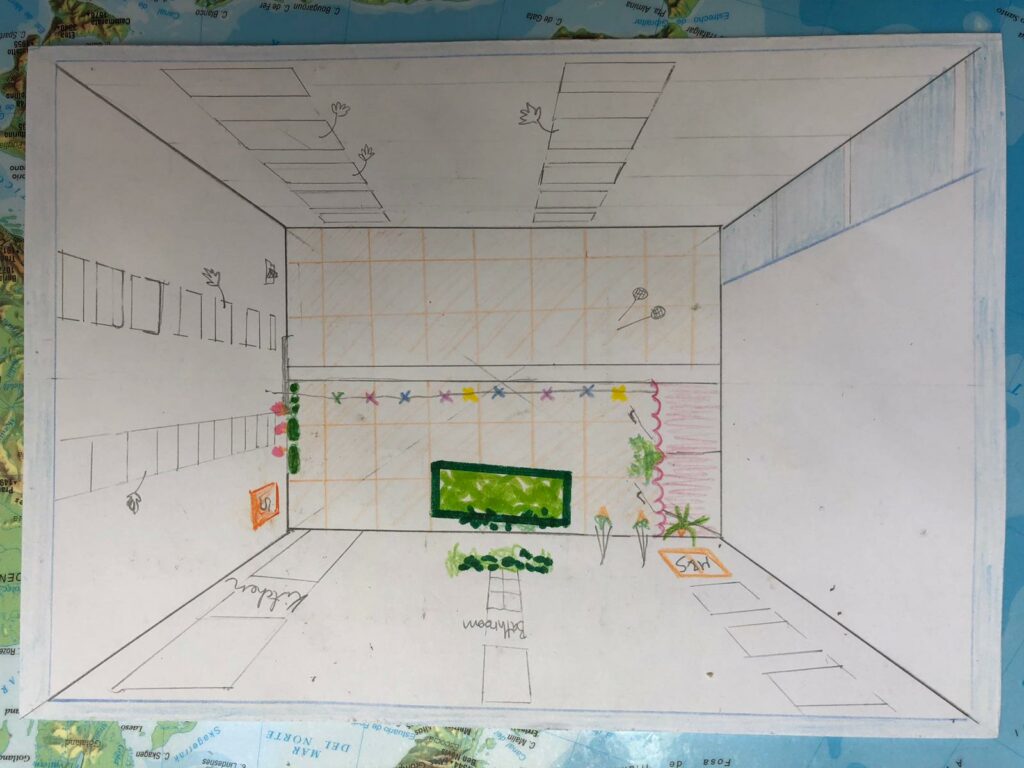

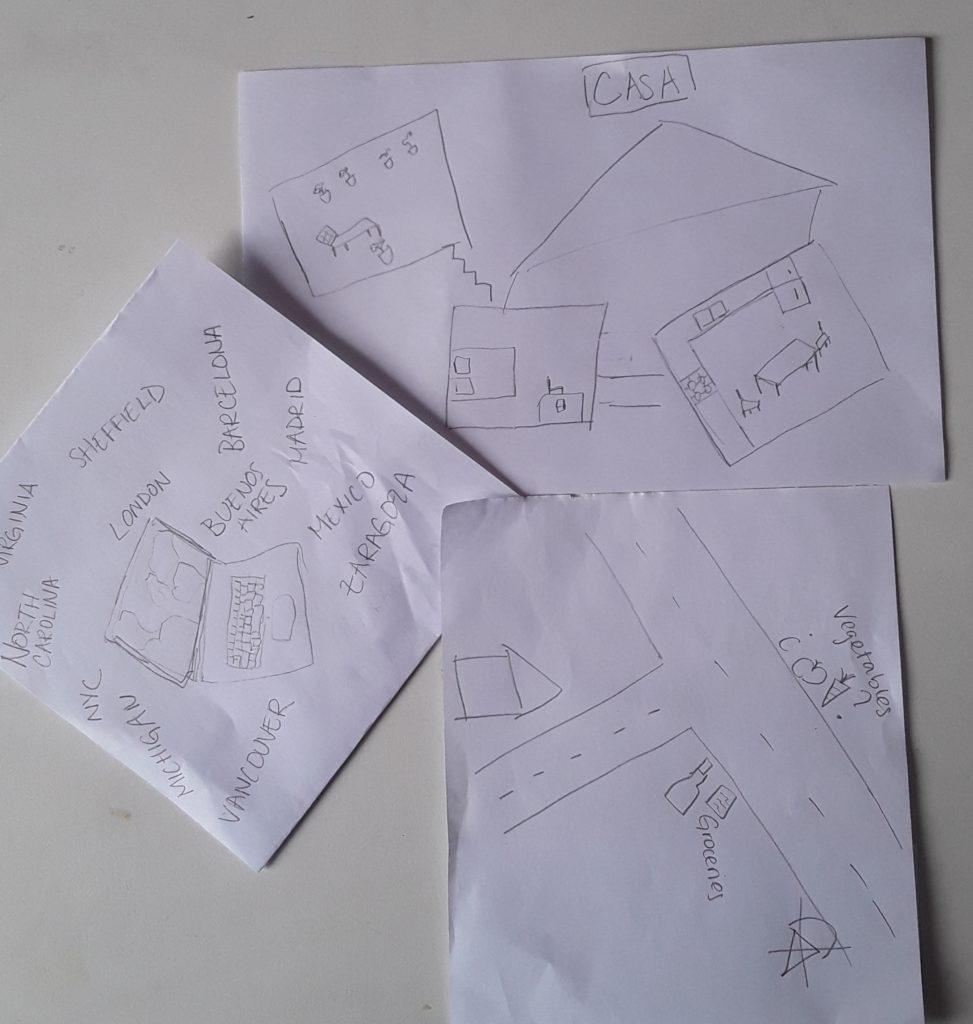

Some quarantine maps

Here we share some of the maps we received from our call for quarantine maps (and we are always open to receiving more!) and highlight a few themes that appeared:

- geographies of fear & anxiety: where and who are we afraid of, where does contagion come from?

- remaking the home (the entire home becomes school, workplace, restaurant, entertainment center, production & reproduction intermix)

- time: stuck between monotony and boredom and an absolute lack of time/overwork/multitasking, watching children/working/cooking/zooming all at once!

- new geographies of debt & extraction: who profits off of us being stuck at home?

- new geographies of mutual aid, care, and resistance in our neighborhoods and beyond!

- geographies of differences: despite claims that “we are all in this together,” we experience the pandemic differently based on how we are positioned in relations of exploitation & oppression, how certain governments responded (or didn’t) to the pandemic, our access to care, etc.

Map your May Day! Quarantine Drifts

The coronavirus and its associated crises, are being graphically narrated by cartographies of the spatial spread of contagion, numbers of deaths, health care capacities, unemployment numbers, etc. We have gotten used to checking those maps in the daily news, feeding our anxieties and imaginaries of contagion, risk, and danger. Yet, what is left out of this type of statistics-based mapping, this perspective from above? And how could we use these maps to share other stories, other experiences, to connect them and to organize? What can we learn from how our daily lives are re-invented inside the differentiated confinement of quarantines? What do the pandemic and quarantine reveal about the previous ‘normality’ and its breaking points? What possibilities for political action are closed off and which open up? And this May Day, we return to an old question, but with a new twist: what is your strike (in quarantine)?

With this in mind, we want to propose a collective mapping of our quarantines, the care chains that we are involved in, and our possible strikes. Make maps either individually or collectively and then please send them to us at countercartographies(at)gmail.com & let us know if you want to be involved in future projects!

Map themes:

1. Map your quarantine! Where do you go, in your house, in your neighborhood or your city? Where do you work? Where and how do you connect with others? How is your mobility limited in this time? Make a time-use chart: how do you spend your days? How much time are you working, caring for others, consuming, anxiously watching the news, etc.?

2. Map your chains of interconnection: whose care and labor makes your quarantine possible? For example, where does your food come from? Where does your trash go? And whose quarantine are you making possible with your labor? Landlords, bosses, Jeff Bezos? What geographies of mutual aid and solidarity are you involved in?

3. Map your strike: What will you stop doing? What will you stop consuming? What will you stop paying?

What has 3Cs been up to?

As we’ve become more dispersed geographically, now spanning three continents, and temporally, with different rhythms of everyday life and precarity and different care and community responsibilities, we often find it hard to work together on big projects. But our collective thinking still informs work that we are all doing and we continue writing and theorizing about maps and counter-maps, precarity, migration, care, and militant research, among other things…

Continue reading3Cs at the Autonomous Geographies Encounter in Ecuador

3Cs was honored to participate in the Encuentro de Geografías Críticas y Autónomas [Critical and Autonomous Geographies Encounter] in Ecuador earlier this year. There we were introduced to a vibrant autonomous geography and cartography movement from across Latin America.

We were hosted by the Critical Geography Collective of Ecuador, which has produced an impressive range of maps with different social movements across Ecuador (related to mining, indigenous land struggles, violence against women, and many other crucial struggles) and a number of pamphlets on critical geography and mapping. (For more about the Collective in English, see their entry in This Is Not An Atlas).

Continue readingA Community Map of Miles Platting

Liz from 3Cs recently participated in a the Community Mapping of Miles Platting in Manchester in collaboration with the University of Sheffield Urban Institute’s “Whose Knowledge Matters?” Project and the Manchester Community Grocer. The process involved a series of workshops with residents of the neighborhood of Miles Platting about how urban redevelopment projects are shaping their neighborhood and the lasting impacts of austerity. The map is currently on display at the Manchester Central Library as part of the Manchester Histories Festival. Here she shares a few reflections from her experience:

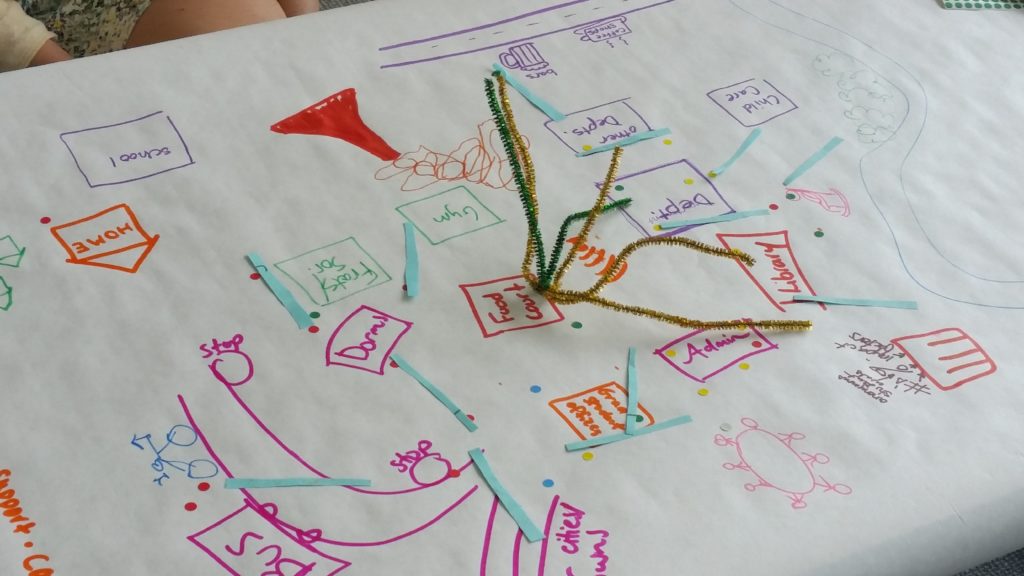

1) Mapping functions as collective research. Making the Community Map of Miles Platting functioned as a form of collective research in various ways. First, it allowed different residents to share the knowledge they already have based on their everyday life and experiences living in Miles Platting. Of course these experiences differ, based on how long people had lived in the neighborhood, their age, gender, race, ethnicity, education level, whether they have children or sick or elderly residents to care for, etc. etc. The first workshop served as a space to share those experiences, without attempting to come up with one dominant narrative, and then to identify common themes and concerns that would then serve as the basis for the icon-stickers we used in the following workshops. Second, the mapping also allowed us to identify new questions and things that were unknown: Who owns that plot of land? What are they building there? What will happen to that abandoned building? Where is the new park they promised us? Identifying these questions served as the basis for further research and also allowed us to question why it was that neighborhood residents didn’t have access to this information. Why, despite promises of consultation and participatory planning processes, were residents not only being left out of decision-making processes, but also not even able to access information about what was going on? Thus we decided to use blue stickers to indicate all of these “mystery spaces” on the map.

Continue readingStatement from the Critical and Autonomous Geographies of Latin America Encounter

3Cs participated in the Encounter of Critical and Autonomous Geographies of Latin America in Ecuador earlier this month where we had the immense pleasure of meeting and learning from other geography and counter-mapping collectives from across the continent. We’ll share more about the encuentro soon, but first we share the collectively written statement that came out of the meeting and that was read in the Encounter of Latin American Geographers in Quito on April 12 (español abajo).

We recognize Latin America as a geography that has been and that continues to be marked by material, epistemological, cultural, symbolic, and gendered coloniality, which continually dispossess peoples of their territories, knowledges, and feelings; and that has impacted our way of understanding our living spaces.

As critical and autonomous collectives that are building plural geographies from and in solidarity with Latin America, in the current context of the advance of racism, fascism, neoliberal capitalism, sexism, and the criminalization of protest,

We reject:

Theoretical and applied neoliberal geography that provides the conceptual and technological tools for the commercialization of education and the dispossession of common goods and knowledges.

Geography that justifies and reinforces the advance of fascism, xenophobia, and colonialism through geographical determinism, ethnocentrism, centralism, and methodological nationalism.

Continue reading3Cs at the Feminist Geography Conference

Last May, 3Cs facilitated a workshop on mapping spaces of precarity and spaces of care at the Feminist Geography Conference in Chapel Hill.

The abstract:

In the Counter Cartographies Collective, we have long been concerned with increasing precaritization in the university, not only in terms of working conditions but also the precaritization of other facets of life and knowledge production. Yet more than a description of current trends, we have understood the concept of precarity as a tool that might allow for remapping new ties of solidarity and the emergence of an ethics of care. In this workshop, we will be collectively mapping out how the university both produces precarity and also serves as a site of resistance to it. We will look at spaces where we feel threatened, isolated, marginalized, or precarious, as well as the spaces of possible or already existing alternatives, spaces where we feel cared for, where community is being built. While we will particularly look at the campus space, we also hope to focus on the connections between the university and other places, such as the home and the city.

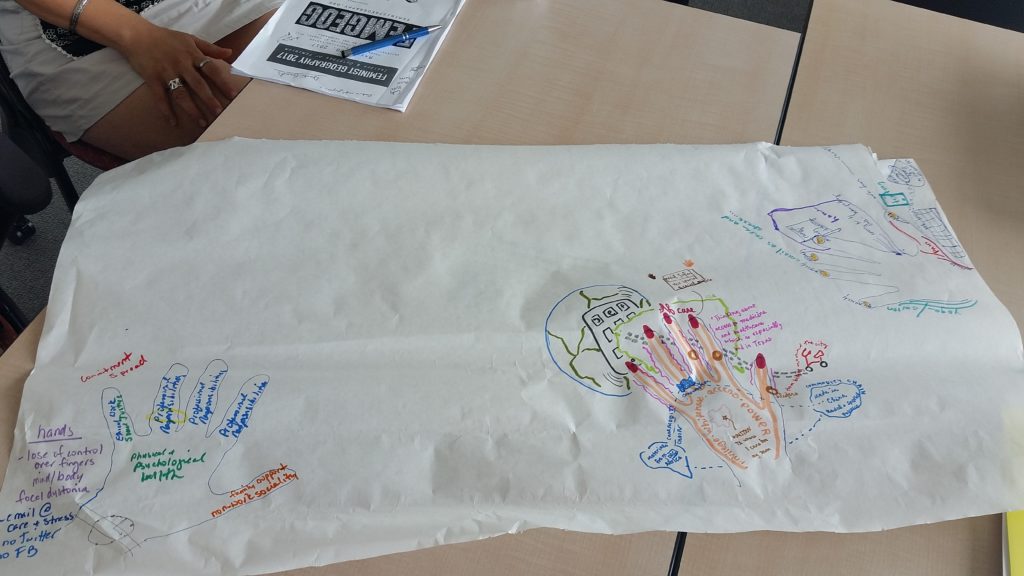

Each group took the prompt in a different direction, deepening our original questions about precarity and care in unexpected ways. One group started by tracing their hands and mapping out their experiences of precarity starting from their hands – arthritis, women typing for men, so many emails – but also of care – painting nails, swimming, yoga, caring for others. [This reminds Liz of her experience of shattering two fingers in a bus accident and being unable to write, cook, open doors or wine bottles, and needing so much care!]

A second group made a concept map linking spaces and experiences of precarity, also showing how different people can experience different places differently — the gym, the forest, the coffee shop, are spaces where some people feel cared for an others don’t. Another group mapped spaces where people feel support and cared for versus spaces of precarity, also highlighting the role of the internet and virtual spaces.

We can draw some initial conclusions from this mapping… First, the importance of bodies/embodiment – both in how we feel and experience precarity and lack of care and bodies carrying out the material labor involved in “immaterial” academic labor, as well as the specificity of different bodies in experiencing different spaces differently.

Second, that the university is routinely experienced as a space of precarity, albeit in different ways, and there seems to be very little opportunity for constructing any lasting spaces or infrastructures of care within the university. What there might be, however, are moments or tactics of care and links to spaces of care outside of the university.

And finally, that care is a lot of work!